Hemingray Blue

By: Arlen Rienstra

Introduction: Glass Colors

Collectors and others who appreciate the various colors of glass insulators and bottles often wonder about the reasons for these variations. And while most early glass insulators and bottles are primarily utilitarian in nature and were produced often with no particular color preference, there remain questions about those glass products that do seem to have a certain color consistency and category.

Research and studies of glass-making processes and products will find that most colors of glass are the result of the presence of oxides of metals within the glass ingredients. A glass batch formula is usually made up of sand, soda ash and limestone as its basics; other ingredients may be added to achieve consistency or color. Early fruit jars, for example, were made from glass using this method at Ball Brothers Glass Plant in Muncie, Indiana:

“The process of making glass and producing jars and bottles in our first open-pot furnace was as follows: The batch consisted of sand, one thousand pounds; soda ash (carbonated soda), four hundred pounds; ground lime stone, one hundred eighty pounds. This batch was mixed on the floor by hand with shovels. The pots were filled with batch in the evening, melted during the night, and worked out during the day.” (*1)

This method of making glass seems rather primitive in nature, as were the methods of forming the glass products early on. And, depending on the origin and contents of the sand used to make up the batch, there was always a small amount of metallic oxides present in the sand, which is primarily silica. These metallic oxides were what determined the color of the finished product. In most cases, unless other ingredients were added to counteract it, the iron oxides in sand would produce a green/blue glass color.

“The most common of all colors in which glass bottles are found are varying hues of green and blue, often called aqua. For thousands of years most of the cheap glasses used in the manufacture of bottles were these colors because of iron in the raw materials, mostly in the sand. Glass makers did know, however, that pure ingredients would produce clear glass; in many where clear glass was demanded attempts were made to purify the raw ingredients. Glass makers even went so far as to crush iron-free quartz crystals to obtain pure silica. Early glasshouses were established with much consideration given to the nearest supply of the purest sand possible, as well as to an abundant fuel supply. Glass can be produced in all colors of the spectrum. Early glass makers knew this could be accomplished by adding certain compounds to the basic glass mixture. The following shows the kinds of materials frequently used and the colors obtained:

copper, selenium, gold = reds; nickel or manganese = purple; chromium or copper = greens; cobalt or copper = blues; iron = greens, yellows; selenium = yellows, pinks; tin or zinc = opal or milk-glass; and iron slag = “black glass”. (*2)

Insulator and bottle collectors have long been aware of a group of insulator designs and fruit jar types that share an identical common color called Hemingray Blue and Ball Blue: an intense, transparent blue that deepens with glass thickness. This uniformity of blue, when compared to other common green/blue glass products, is found almost exclusively in the insulators and fruit jars produced by Hemingray Glass Company and Ball Brothers respectively, both with factories in Muncie, Indiana. The products had other commonalities: they were produced in about the same span of years (approximately 1900-1920), with newly-developed automatic forming machines, and from newly-developed and utilized continuous feed glass furnaces. Another fact common to both products was the location of the two glass companies: both on the same street, directly opposite each other.

But, none of these common production similarities would in itself be responsible for the blue-colored glass products. Further investigation finds that both glass manufacturing companies used a batch ingredient purchased from a common source. The sand used by both had the same origin: Michigan City, Indiana.

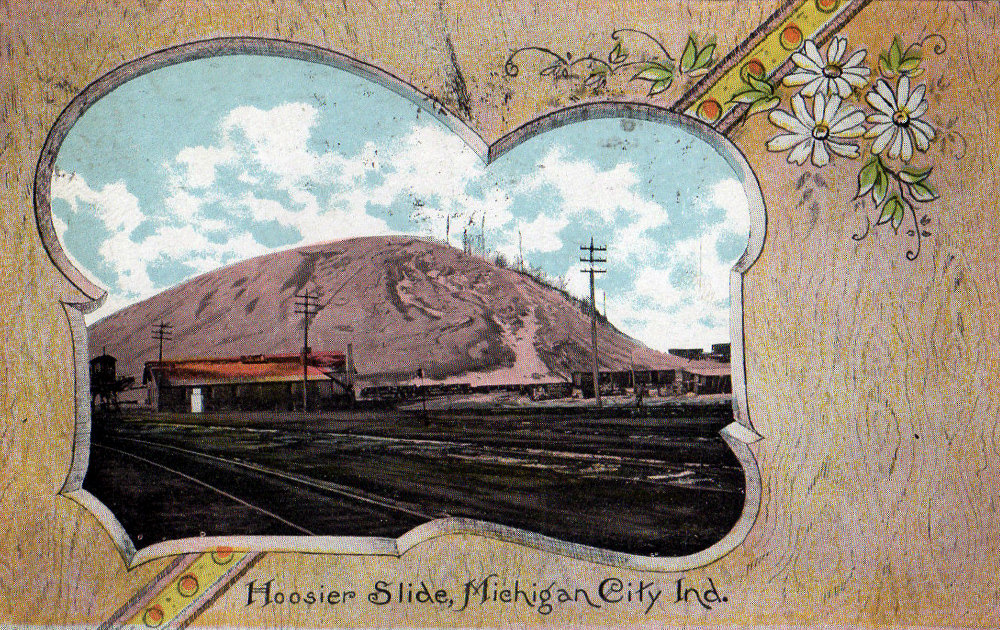

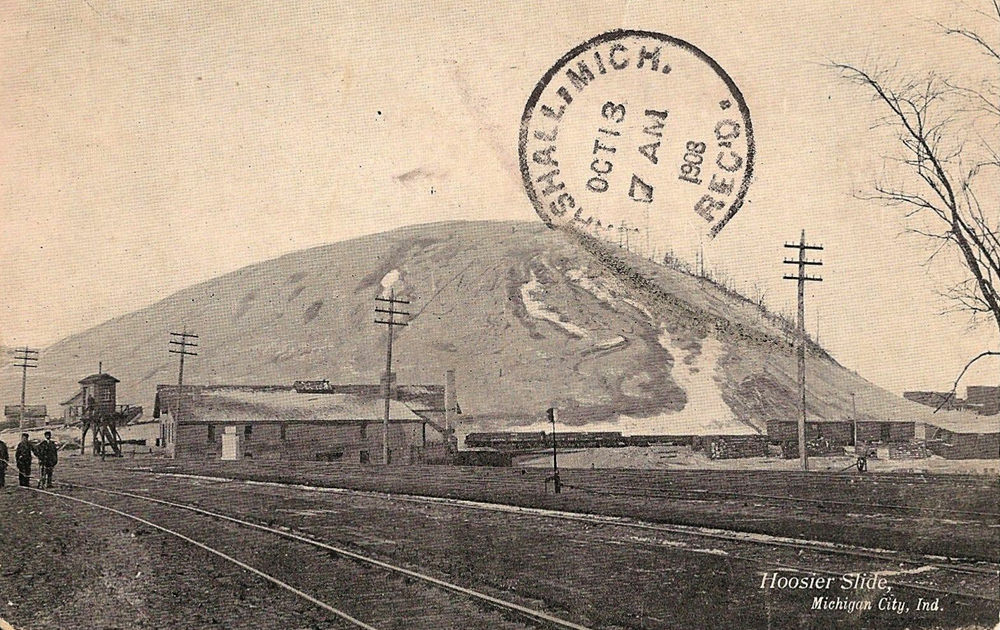

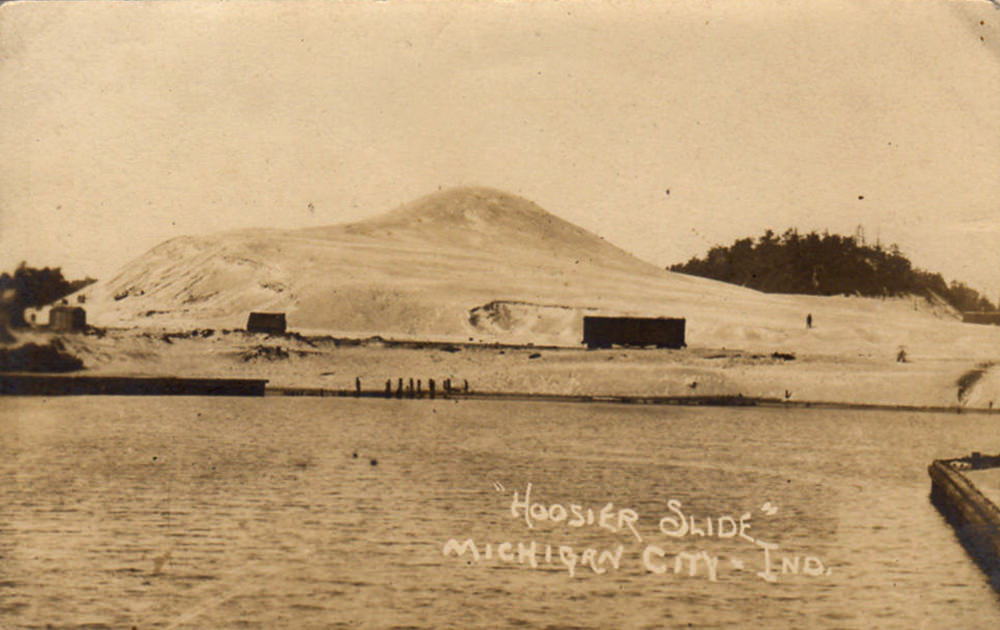

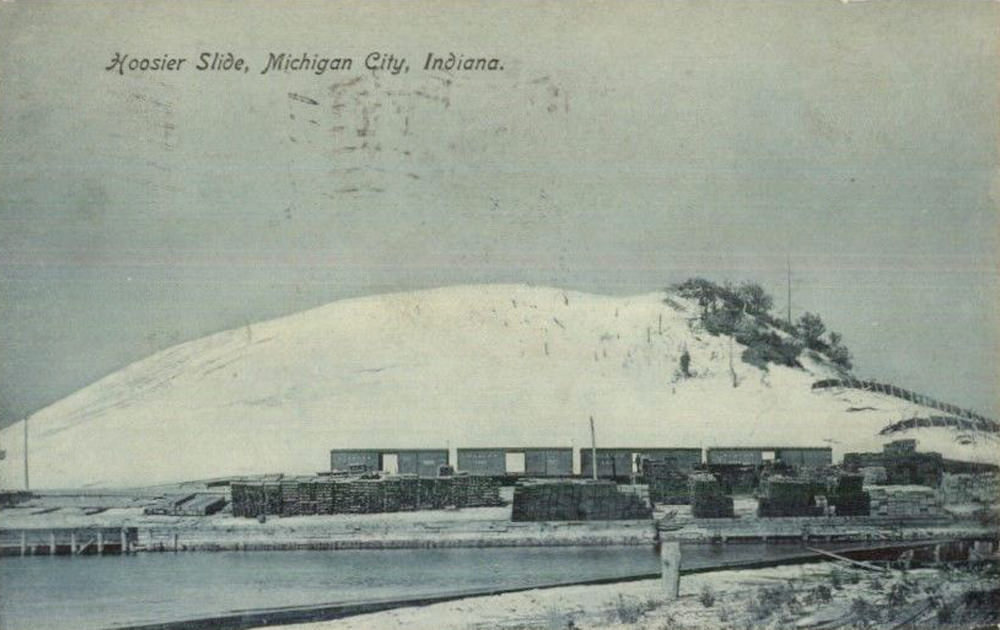

Hoosier Slide

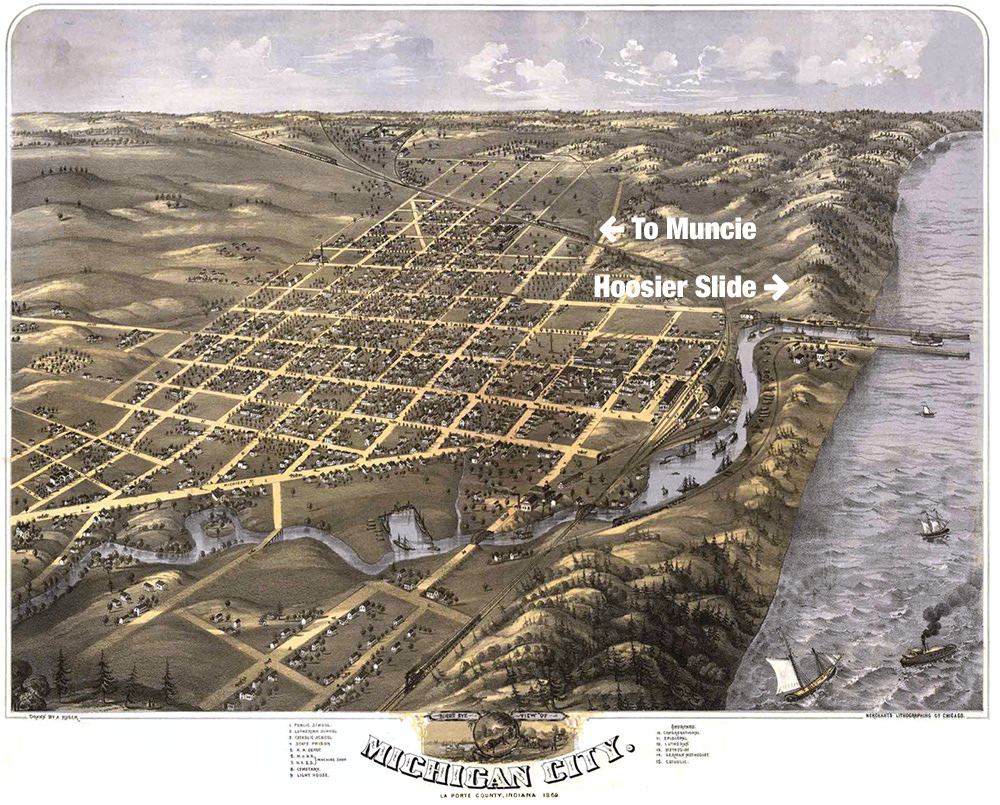

Michigan City, Indiana, is a harbor town on the south shore of Lake Michigan, near the Michigan state border.

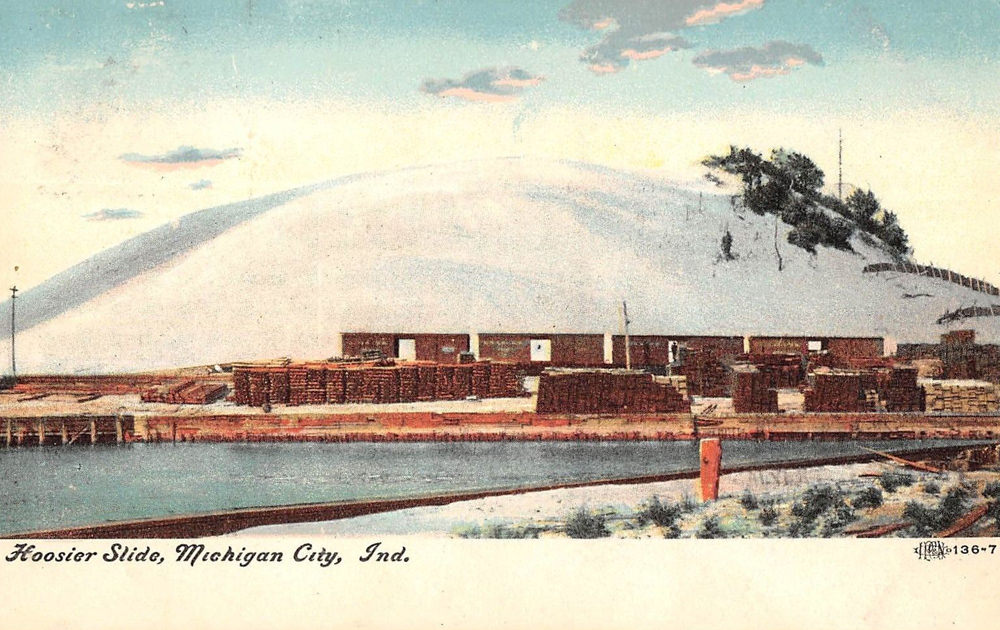

It is located northwest of Muncie, Indiana, approximately 170 miles by rail. Large sand dunes are indigenous to the shoreline at Michigan City, and for many miles east and west. In its early days, the area was recognized as an important port on the lake for loading and shipping of the many natural products of the Great Lakes region, both by water and by land. Over time, the Trail Creek mouth on the lake was expanded into a fine harbor and railroads were built through the area. Lumber and sand were two of the nearby resources available, and manufacturing and industry grew rapidly there, also.

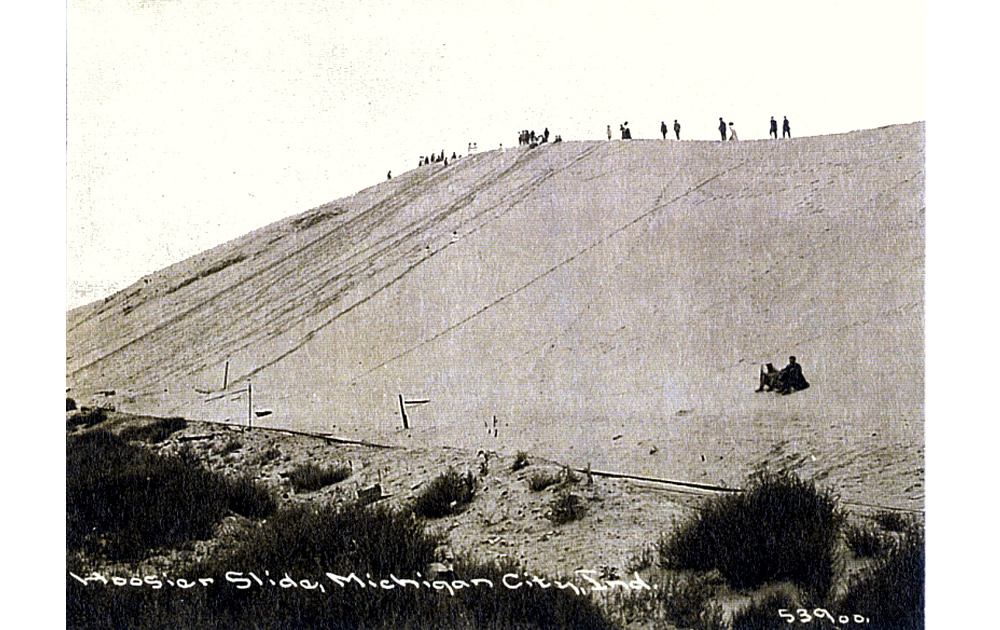

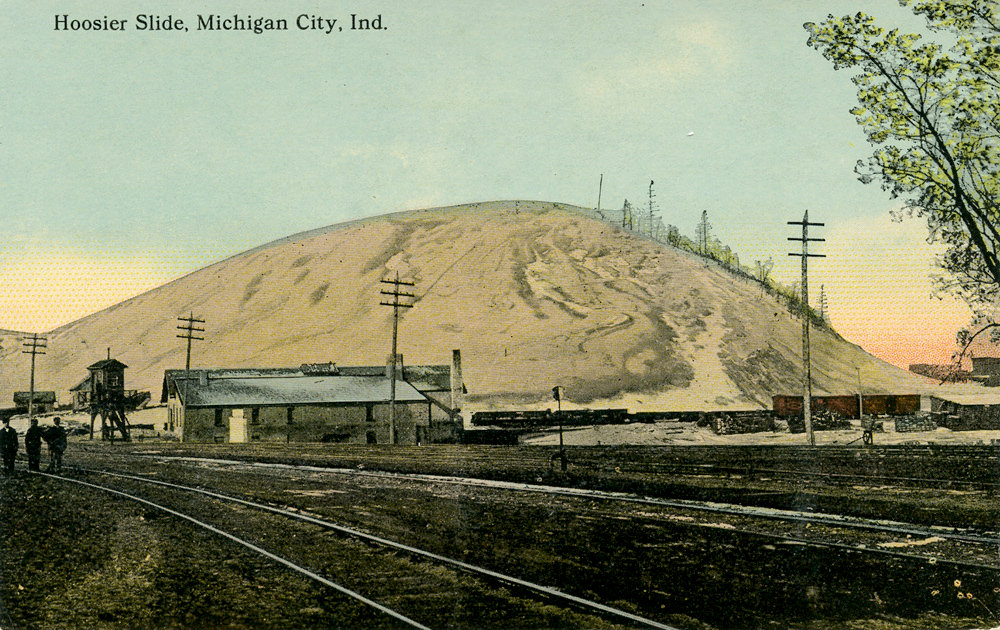

The largest sand dune was just west of the harbor. Once Indiana's most famous landmark, Hoosier Slide (aka Devil's Slide), was a huge dune bordering the west side of Trail Creek where it entered Lake Michigan. At one time it was nearly 200 feet tall, mantled with trees. Climbing Hoosier Slide was very popular in the late 1800's with the excursionist crowds who arrived in town by boat and train from Chicago and other cities. The summit, where weddings were sometimes held, afforded an excellent view of the vast lumberyards which then covered the Washington Park area.

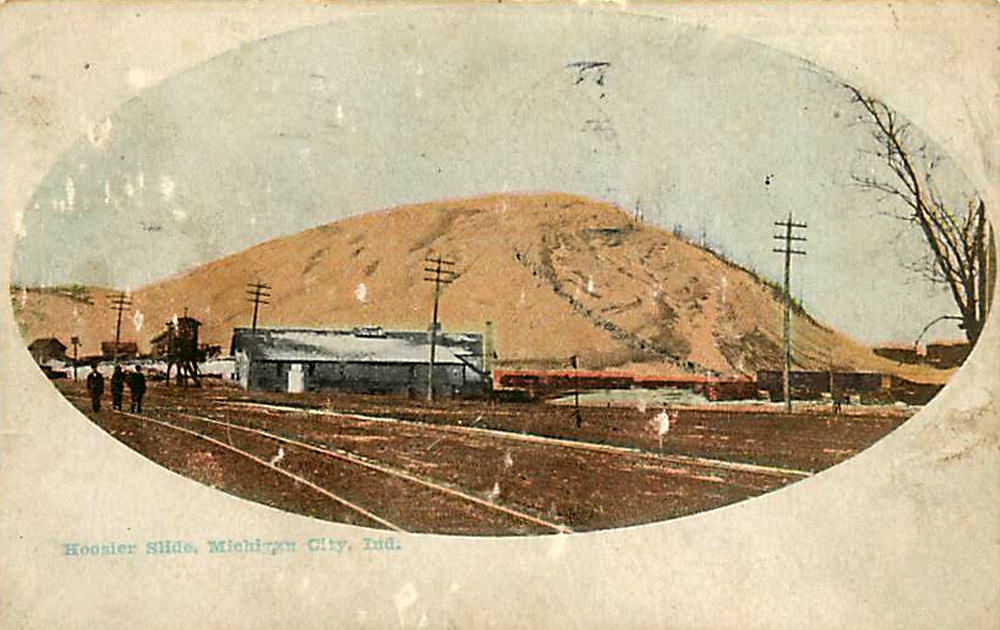

In the mid 1800s, the dune had trees and berries, cows even grazed there. As the trees were cut and used, the dune became bare, probably by 1870. Commercial sand mining began about 1890, when the Monon Railroad built a switching track along the south side of the dune, to serve the lumber docks along the west side of the harbor. The sand was loaded in wheel barrows and pushed across planks to the gondola cars - this being done mostly by the 100 or so dock workers, and their families. These dock workers’ main job was to unload lumber, corn and salt from the incoming ships. The sand mining was done in between ships.

Around 1890, natural gas was discovered in central Indiana, and glass factories started in the Muncie area. Large users of Hoosier Slide sand were the Ball Brothers and the nearby Hemingway Glass Co. in Muncie, and Pittsburg Plate Glass in Kokomo. As cars and mechanized farm equipment became more popular, core sand for foundries became another use for the sand. Core sand was shipped as far away as Mexico. Much of the sand also went to Chicago in the 1890's as fill for Jackson Park and for the Illinois Central RR right-of-way.

The two major sand companies, Pinkston and the Hoosier Slide Sand Co., became very competitive, and the use of cranes and electrical conveyor belts escalated. The sand removal was especially heavy during WWI. Over 30 years, approximately 30 railroad carloads were shipped daily-a total of 13.5 million tons, until the great at dune was leveled. NIPSCO acquired the site for use as a generating plant in the late 1920's.

The following report of the sand companies relates the importance to business of Hoosier Slide sand:

Hoosier Slide sand presented an opportunity for financial gain beyond its lure as a tourist attraction. W. B. Manny became interested in the market for sand which was being made into glass in East-Central Indiana. There the sand could be made into glass easily with the high heat generated by natural gas. In 1906, the Hoosier Slide Sand Company was incorporated. Tracks circled to the north side of the Slide, and shacks were built nearby for the sand pit loaders. They first moved the sand with shovels and hand wheelbarrows. The Pinkston Sand Company was offering Hoosier Slide sand for 20 cents a ton in Foundry Magazine as early as 1907. In the 1920's the S. J. Taylor Sand Company had a spur line from the South Shore tracks to a sand mining operation east of Mount Baldy and west of Hoosier Slide. Locomotive cranes had taken the place of wheelbarrows, The carloads of sand were shipped over the Monon and Michigan Central railroads. The local sand companies where shipping to the Ball Brothers in Muncie, Indiana, for the manufacture of fruit jars; to Westinghouse Air Brake; to Pittsburgh Plate Glass for foundry products, and to Hemingray Glass Company for the manufacture of insulators for power companies, and for telegraph and telephone companies. (*3)

Another account, from an 1891 Indiana newspaper, gives this account of the mining of the Slide:

"HOOSIER SLIDE." - AN INDIANA LANDMARK GOING TO CHICAGO.

An Interesting Letter from the Lake - The Fate of "Hoosier Slide" -

[Special Correspondence.]

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind., May 16.--Your readers may be surprised to learn that "Hoosier Slide" is disappearing, but such is the fact. It stood for ages, perhaps, looking out over the blue waters of Lake Michigan and though fashioned out of "shifting sand," but little change was noted in its lofty appearance. The east line of its summit was the highest point and a scrubby tree used to stand up there. Such might have been the case to-day had not a CHICAGO man come along and purchased that pile of sand. Chicago men never do something for nothing. This genius bought the "slide" at wholesale and immediately began to sell it at retail. The sale continues and this accounts for the disappearance of the famous mound. A force of men are at work six days in the week shoveling the sand on to flat cars for railway uses, and as they burrow into it at the foot, it rolls down from the top. It is a mountain of sand yet and will be for years to come--even should the shoveling process go on. But even now the east line is no longer the highest point. The scrub tree is gone, the shape of the whole top has changed and what is now the chief outlook was a year ago a secondary point.

"Hoosier Slide," like any other slide, is treacherous. If there were an inch auger hole at the lowest point of the "slide" and a sufficient vacuum beneath, the whole mountain would proceed to pass through that hole without stopping. It is said the Chicagoan is getting rich. Well, he will leave an opportunity for his grandchild to get rich from the same pile of sand. Nevertheless, the crest of "Hoosier Slide" is lowering in a marked manner and the busy shovel will yet bring it to the level of Michigan City, which lies at its feet.

By the way, speaking of Michigan City, it is one of the most wide-awake cities in the State. Once it was a tempest-tossed sand lot. Now it is a beautiful city . . . (*4)

An account entitled “1914 Michigan City Sand” reported that:

Several of the glass sand industries of the State use this sand in the manufacture of glass products. Notable among these is the well-known firm of Ball Bros. of Muncie, Indiana, manufactures of jars. This company has been using sand from Lake Michigan for about twenty-five years and it has proved satisfactory. This sand has the advantage of freedom from the usual impurities which accompany indurated deposits, for the reason that it comes ready washed from the lake. Ball Bros. use about 150 tons of this sand per day. Their products are shipped to all parts of the world. (*5)

-

Hoosier Slide - 18xx

-

Hoosier Slide - 19xx

-

Hoosier Slide - 1898

-

Hoosier Slide - 1906

-

Hoosier Slide - 1907

-

Hoosier Slide - 1908

-

Hoosier Slide - 1909

-

Hoosier Slide - 1910

-

Hoosier Slide - 1913

-

Hoosier Slide - 1915

An Analysis of the Sand

In the same report, an analysis of the glass sands of Indiana by the Indiana Dept. of Geology and Natural Resources (1914), shows that the sand from Michigan City was unique among 13 other sand sources analyzed from around the state. It shows that the silica content was least of those analyzed at 91.98 %. The sand was third highest in Alumina at 4.44%; very low in Ferric Oxide (iron) at .56%; highest of all in Calcium Oxide (lime) at 2.20%; and with only a trace of Magnesium Oxide (a glass clarifier).

With such a low percentage of iron, a high percentage of Alumina, and very little Magnesium to affect the color, it seems quite possible that this is the reason for the unique blue color of the glass products of both Hemingray Glass Co. and Ball Bros. Co. The high amount of lime (a flux), must have helped the glass batch to melt easier and at a lower temperature. This would make the sand very desirable to any glass-making operation.

Regardless of sand analysis and mineral content, the sand from Hoosier Slide and Michigan City was also sought by users because of its cleanliness and lack of organic matter content. Many foundries purchased it for use as molding sand in casting metals into sand molds. It was also noted in the report that the sand was useful as grinding sand, which was used in jar-making to finish the top lip of blown-in-the mold fruit jars, before the advent machine-made jars.

Conclusions

The evidence for the sand source for both Hemingray and Ball being that of Michigan City, more specifically Hoosier Slide, is circumstantial, yet convincing. Though records from the two glass companies have not been found to indicate which of the mining companies shipped to them, the fact that it was shipped to them from Michigan City is clear. The time period from the beginning of the intensive mining operations in the late 1890's to the depletion of Hoosier Slide by1920 corresponds to the same time period in which the Hemingray Blue and Ball Blue glass products were manufactured.

Most of the Hemingray insulators of this unique blue color are embossed “MADE IN U.S.A.”, a practice which began about 1914 with laws requiring imported products be marked with country-of-origin. Hemingray was eager to export its products and so conformed to this new practice. Studies of insulator and jar styles and embossing comparing them to their time span of production also indicate a matching of product and sand source time lines. Ball jar collectors have studied the script style of the “Ball” logo on jars to definitely determine the years of production of “Ball Blue” jars and correlate them to the same time frame of sand importation from Michigan City's Hoosier Slide. In fact, jars produced by other Ball plants (purchased from competitors and using their remade molds and glass batch ingredients) other than at Muncie are definitely not the same blue color, even though produced during the same period.

Photographs accompanying this report and display show the Hoosier Slide and sand mining operations. Postcards of the period also demonstrate the enormity of the sand deposits on Lake Michigan at Michigan City and the attraction it was to tourists and excursion groups. These views are all that is left for evidence of the existence of such a wonder, except for for the unique blue-colored products of two glass companies which used the sand to produce them.

Hemingray Blue Insulators

For a complete list of all known Hemingray made Hemingray Blue insulators see this page.

Credit

1 = Memoirs of Frank Clayton Ball, 1937, Muncie, Indiana.

2 = My Research on Glass Colors - Cecil Munsey, PhD, Copyright 2000

3 = Indiana – The Life of a Town, Gladys Bull Nicewarner, Copyright 1980

4 = Lafayette Morning Journal, Monday, 18 May, 1891

5 = 1914 Report – Page 49 by Indiana Dept. of Geology and Natural Resources, Indiana Dept of Statistics and Geology – Botany

Insulator Photos = Shaun Kotlarsky

Share this page on:

Like or Follow on Facebook: